"Intuition" Talk

Vacuous at best, Dogma at worst

I have talked about the scope of formalism, inference schemas and “rationality” in disputes before. I shall continue to do so as there is much more to be said. In this piece, I wish to clearly express my thoughts about a move that is made in disputes where interlocutors invoke “intuitions” as justification cheat codes for their relevant positions.

Let’s use a model dispute to centre our thinking. In the following conversation Joe Rogan and Matt Walsh1 disagree about whether or not gay marriage is morally acceptable:

I shall boil the dispute down to the following:

Walsh:

”If my Catholic theology is correct then gay marriage is wrong

My Catholic theology is correct

Gay marriage is wrong.”

Joe:

If you dont have arbitrary prejudices gay marriage is OK

You shouldn’t have arbitrary prejudices

You should believe gay marriage is OK.

I have lovingly labelled this interaction “Joe Rogan DESTROYS Matt Walsh with pre-schooler intuitions”. Of course, none of what I am saying here is verbatim from this clip. Try to keep in mind that it really doesn’t matter that much what you think about the topic of gay marriage, Joe-Ape-Man-Rogan or Matt-Catholic-Guilt-Walsh. I want to make points about the role of “intuitions”.

Let’s consider the scores then. We start at Rogan 0-0 Walsh. Both disputants provide us with a single reason in favour of their conclusion bringing us to 1-1. Nothing decisive here then.

Suppose, when pressed by Joe, Walsh now provides us with some “new” information. He insists “the first two premises of my argument are intuitive … not believing P1 and P2 of my argument is counterintuitive and utterly crazy”. Walsh has now provided us with additional reasons, he’s 2-1 up. He managed to say more sentences which weigh in favour of his conclusion. It gets worse for Rogan, Walsh has actually had a sabbatical from producing the newest Daily Wire Propaganda movie, Lady Ballers 2: Is it gay if she’s hot? and has actually picked up a book. Unfortunately, (as nice as the author is) Walsh picks up Michael Huemers Skepticism and the Veil of Perception2. In there he reads

(PC) If it seems to S as if P, then S thereby has at least prima facie justification for believing that P.

Walsh, a man of honor and anti-woke rationality (much like Huemer as of late) turns to Joe, well-prepared to bring out his philosophical big guns.

Walsh: “I merely believe in the modest epistemological doctrine of phenomenal conservatism, and it seems to me that my Catholic theology is correct, and if my Catholic theology is correct then gay marriage is wrong!”

I’m not sure if there’s a score multiplier for the use of such intimidating words as “epistemological doctrine” whilst simultaneously expressing one’s epistemic humility and virtue with the use of the modifier merely, needless to say the score at this point is at least Rogan 1-3 Walsh.

Is it that easy to “win” philosophical disagreements when we equip ourselves with Phenomenal Conservatism? Consider the following claim: given that a person reports some statement, p this entails that p seems true to them — for what else can “seem” here mean that when they are asked to reflect upon p they assent to it? Perhaps there is some ramified account of seemings which makes appeal to queer entities, faculties and the rigorous methodological apparatus of analytic metaphysics. I shall leave such fascinating accounts for authors of international best-selling books and truth-seekers alike, but whatever such theories may have to say, they will all involve persons assenting to p. When they reflect upon p they agree, they will answer questions in such a way that they say “I believe p”, “yes I think that p is true”. They will not say “it seems to me that p but p is not true and I don’t believe it”3 I believe that the entire plausibility of PC falls upon considering these cases, considering a few simple cases where we use “seems” and “intuition” language to assent to statements and then reading off of that a normative epistemic principle which we can then appeal to as if it were inscribed in Stone atop Mt Sinai to double-count our reasons for beliefs we hold.

The problem with all this is the transparency of “intuition” and “seems” talk4. If I am correct, as I usually am, and indeed it seems to me I am, then commitment to any statement, the fact that a person has positively assented to a statement is sufficient to entail that that statement seems true to them. I have come up with a new principle to describe the transparency of intuition talk. It seems to me, such that I have an intuition that Karl Marx was talking about metaphilosophy when he said “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”5. And as it is with material resources, so it goes with intuitions. As such, I shall call my new principle PC; Phenomenal Communism, i.e. as revolutionarily opposed to Conservatism as one can be.

(PC) Phenomenal Communism: If S reports any of {P, P is true (or similar) } then it is also true that it seems to S that P

Intuitions come cheap! If we apply Hegelian science to Phenomenal Communism and Conservatism to achieve the ultimate synthesis, vis a vis epistemic principles for based Prussians at the end of time, we find the following.

We have considered reports of p as entailing intuitions of p, AND we have permitted that intuitions of p count as justifications of p and we have constructed an infinite justification redistribution machine via the science of Marx’s thought; who said Continental philosophy was useless?

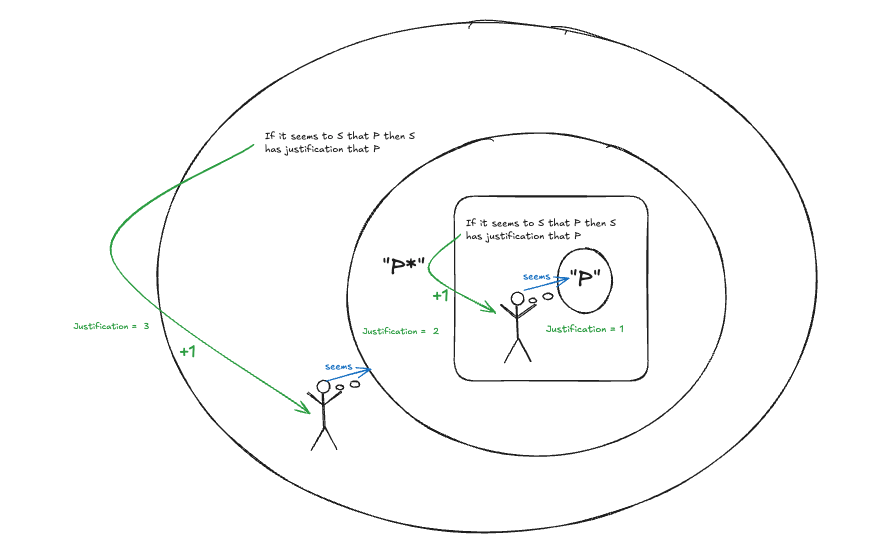

This is because once we have committed to p, philosophical communism provides us with the intuition of p, philosophical conservatism then gives us a +1 justification for p. Now we know all that we have some new set of statements (a la Matt Walsh) p* that we can now produce in defence of p. Namely, our deployment of philosophical communism and conservatism with our justification for p. We take this entire description as a new statement p* and because we believe p* we have an intuition that p*, and so we have a +1 justification for p*. Hey presto! Infinite justification glitch unlocked. Of course, I think talk of “+1” justification is absolute nonsense, but it’s nice to throw a spanner in the works to make any intuition proponents who read this pause for a second to think about what the hell they’re saying about justification and all that rather than bloody mystic Meg-ing it out of The realm of True thoughts.

If this line of thought is correct, then we can take “seems” and “intuition” talk as vacuous. Parasitic upon the claims it purports to be “about”, transparent, argumentatively flaccid. Further, the claims that these intuitions are parasitic on are still susceptible to deconstruction and interrogation.

I think it is true that the past history of the universe is finite. It seems true to me. I have an intuition based on further claims I have intuitions about. However, if a physicist came up to me and provided me with some information I don’t have (even if I don’t know what that may be), or interrogated my concept of “past history” in a way that undermined the question I could psychologically entertain it and potentially my model of reality would shift such that I would not assent to this claim nor would I have my original intuitions. The fact I have intuitions here does not say anything about the possibility of me changing my mind or deconstructing my position. That’s all up for grabs.

Suppose I reject all that, I think that intuitions are not vacuous and transparent. What role do intuitions play then? They play their role in this foundherentist, rationalist justificationist thingy whatsit story. The discursive purpose of intuitions then is to entrench us in our initial position such that we are not moved by counter-argument or consideration. You might even say that the phrase “I have a seeming that” operates as a thought-terminating cliche given its use prior to consideration of alternative ways of viewing things. Phenomenal Conservatives will say this is all unfair. They always caveat their view with the addendum “(PC)… absent any defeaters” — the problem with this is that the defeaters they are presented with always happen to conveniently be the ones they don’t find (i.e. that don’t seem) plausible to them. Intuitions come cheap and are the upshot of (or even identical to assent to) considerations about the claims under discussion. The used car salesman, paid for lawyer, politician and disinterested inquirer into Truth are all in the same position with respect to acquiring this sort of convenient, intuitive justification.

I have argued thus far that intuition talk in this manner is either vacuous and therefore useless for furthering discourse, or an attempt at bootstrapping our claims into ThE FaBrIc oF ReAlItY through special faculties and entities such that it is a malicious discursive trick that ought to be avoided lest we be trapped in whatever claims we started with. i.e. one of the purported claims of philosophical inquiry (by me at least) is to bring pre-theoretical commitments and prejudices into question, to try to build better models of things and figure out what’s true — not to construct a concrete bunker around wherever we happened to start.

In a recent post6 around the argument from psychophysical harmony, Lucas Collier, Sebastian Montesinos, Benjamin (Truth Teller), and Joseph Lawal (henceforth the guys) called these sorts of moves “Intuition Mongering” and described the practice as encouraging a mode of philosophy “as a series of Moorean Shifts Between Two Guys That Can’t Be Wrong”. I highly recommend giving it a read. I shall include a few of the points salient to my post here that I thought were particularly helpful and articulate.

intuitions and their role as justifiers (assuming they have such a role) are private and agent-relative—what appears obvious to one need not be so for another…

[intuition proponents] assume that intuitions, on their own, provide any non-theory laden justification for a belief with no independently motivated conceptual framework or inferential support to wear the trousers…

The proposition "[my interlocutor] has an intuition that P is obviously true" does not entail that P is in fact true, probably true, or even more likely true than before…

we are well within our epistemic rights to not take such intuition-mongering seriously.

Lucas describes why, according to his metaphilosophy, the entire programme of intuition-mongering is deeply mistaken

Despite the rationality of our arguments and the clarity of our intuitions, we are never free from our epistemic contexts: our times, our places, our neurons, our languages, our concepts, our bookshelves, our histories, our mothers, and so on. What is clear to us in one epistemic context might be opaque after our perspective has changed. One aim of good arguments is to bridge these epistemic contexts and allow us not only to solve a problem as currently understood, but reshape the problem itself…

This is why I am skeptical of the “intuition-mongering” outlined [previously] which takes everything for granted and dismisses out of hand arguments and riddles alike. Its users loudly cut their way through philosophical cloth to leave perfectly intuition-shaped holes, becoming ever more sophisticated without ever seriously wondering whether they are metaphilosophically mistaken.

The point is this: someone who views philosophy of mind through a Chalmersian lens cannot and should not estimate the plausibility of a viewpoint as disparate as Paul Churchland’s on something as miniscule as zombies. Any serious look at the issue is holistic: his view of zombies is one brick in a house, and not one brick goes untouched by problems in the philosophies of language and science, epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, etc. To state, as Adelstein does, that Churchlandian eliminativism is “extremely implausible” because of its denial of one loaded proposition is to appraise the house’s value based on the appearance of just that one brick. It amounts to nothing more than reiterating one’s current epistemic context in the register of modus-tollens.

I highly recommend engaging with the entire series of posts and responses and hope the authors make their way to substack ASAP.

This criticism of a specific engagement though has become a common occurrence in my interactions with those who take a different metaphilosophy to myself. Consider this recent interview with Brian Cutter on Psychophysical Harmony7

At 27:05 Cutter responds to Functionalist objections to his argument (views I am very sympathetic to, were it not for my bias against Cognitive Psychology — Long Live Frank Skinner). Cutter outlines how these views undermine the assumptions required for his argument to work, what does he say in response?

Cutter:

27:30 [functionalism] is not plausible (even though it would solve the [alleged] problem of psychophysical harmony.

28:45: [functionalism] would solve the problem but I think it's just independently IM implausible

28:52: whether or not you’re having an experience that's intrinsically bad or that you have reason to avoid uh doesn't depend at all on its functional role

Note here that “intrinsically bad” requires Cutters view of mind and essences to be correct and “doesn’t depend on its functional role” is simply to say that the content of the theory of functionalism is false — why is functionalism, the view that conscious experience are characterised by their functional roles, false? Well, because conscious states aren’t characterised characterised by their functional roles. This is simply question-begging, so why think that?

Well here’s the reason. Imagine yourself as a non-functionally instantiated mind (a thought experiment that you will note, makes no sense if your imaginative capacities and beliefs are informed by a commitment to functionalism) well then if we imagine a demon torturing you (in some non-physical, non-functional, non-process way — ??)

29:27 it's still nonetheless obviously true that when you're in excruciating pain like you're in a state that's bad yeah

Not only is there a way things seem, an intuition about a case Im not even sure what it means to imagine here, but we have an OBVIOUS intuition (which maybe counts for 2x phenomenal conservatism justification units). Functionalism destroyed, and to think I was stupid enough to read a bunch of neuroscience, computer science and psychology to try to understand mental phenomena without having considered this!

And why is a priori physicalism false?

32:35 it predicts falsely that zombies are inconceivable, uh it predicts falsely that Mary doesn't learn anything new when she goes out of her room and experiences red for the first time, um it it predicts falsely that inverted Spectrum scenarios are inconceivable.

Predicts? PREDICTS? Where is this completed neuroscience? Where is Mary? What did she report? When was this experiment performed? What was the outcome? Oh, wait, you mean that you imagined the outcome you required again? And now you have an intuition for that? You can see how this way of doing philosophy costs nothing, requires no difficult work and it grants you everything.

As you may be able to tell I’m making myself frustrated engaging with this sort of stuff and it’s especially frustrating given that philosophers take themselves to be people who critically think about these things and analyse thought.

If something seems too good to be true it usually is, and Phenomenal Conservatism writes cheques it can’t cash8.

Huemer, Skepticism and the Veil of Perception, 2001, https://web.archive.org/web/20110514084610/http://home.sprynet.com/~owl1/book1.htm

If I recall there is a discourse involving Russell, Wittgenstein and G E Moore on statements of this form that I cannot be bothered to dig out — perhaps someone knows

Or, God forbid, the locution “I have a seeming” prevalent amongst those infected with analytic philosophy— sorry, “have” a “seeming”, and of what does this “having” consist? What is this “seeming” made of? Proposition gloop?

Marx 1875, Critique of The Gotha Programme

Intuition, Metaphilosophy, and Psychophysical Harmony: a Response to Bentham's Bulldog, December 12 2023 https://naturalismnext.blogspot.com/2023/12/intuition-metaphilosophy-and.html

A very thoughtful post--entertaining too! But I don't think I agree with it, so I'll just note some responses.

I'm not sure that my assenting to P entails it seeming to me that P, or vice versa. For example, it might seem to me that it would be wrong to steal the organs from one person to save 5 people, or something, but if I'm a utilitarian, I would no longer believe that it's true. But surely it would still seem to me that it would be wrong, I would simply have other, stronger convictions that entail the falsity of this.

If this is right, then it's a case where I assert the truth of P (P=it's not wrong to steal the organs), but it doesn't seem to me that P. And of course likewise that it seems to me that ~P but I don't believe ~P.

Maybe you want to say that this just couldn't be the case. After all, if your considered judgement is that P is true, then your "considered seeming" must also be that P is true. Fair enough, but from introspection I think that I have things that I believe even though they don't seem right. Even if considered seemings are real, it seems (sorry) like seemings change more slowly than beliefs. In the utilitarian case, I may even eventually have the theory so thoroughly integrated in my thinking that stealing the organs no longer seems wrong (though I have a hard time imagining that), but I think that would come a long time after actually assenting to the truth of utilitarianism. So I think there will at least be some period of time where the two don't coincide.

I still think your argument about recursive justification is interesting though. As a first pass response, I guess I would draw an analogy to the truth predicate. Let's say that the fact that this post is good is evidence that you're a good writer. Then surely "it is true that this post is good" is evidence that you're a good writer, and "it is true that it is true that..." etc.--infinite evidence glitch again! But that of course isn't right. Whatever response you give here, I would guess a similar thing could be said about intuitions.

In the Walsh-Rogan case, I guess I wouldn't say that Walsh provides a new argument when he says that the premises are intuitive. Rather, he simply reports his reasons for believing the premises. Suppose that we're debating whether you're a good writer. I give the argument:

1) This post is good

2) If this post is good, you're a good writer

3) So you're a good writer

If I then say in support of 1 "I read the post and thought that it was good", that doesn't give further reason to believe 1--it's simply a report. Likewise I can then cite litterary conservatism: "If S finds X good upon reading it, that is defeasible justification for X's being good". This again doesn't give extra justification. Nonetheless, this also doesn't mean that I'm not justified in judging you a good writer. Intuitions are supposed to be internal sources of justifications, and so, like my finding your post good, reporting them won't give evidence for another person, except insofar as it serves as some sort of testimony. Maybe reporting my intuitions will also help you realize that you have the same intuitions, making the reason *you* should believe the thing in question apparent--after all, we aren't aware of all the relevant reasons at all times.

You include a quote that suggests this should be a problem, but I don't think it is. I take it that an argument should only have persuasive force for you to the extent that you agree with the premises. If I present you with an argument against some proposition you believe, you will only be persuaded if the credences you have in the premises are inconsistent with the credence you have in the conclusion.

Suppose that Walsh and Rogan were--per impossible--to figure out *all* of the implications of their views, presenting all possible arguments against each other's views, such that the other person had some credence above zero in the premises. They would consider all these arguments and adjust their credences and beliefs accordingly. Assuming that they still didn't agree, each person would end up with a set of propositions where no new argument could rationally persuade them--Walsh would believe P and Rogan would believe ~P, and that would be the end of the story; they would just have differing brute intuitions.

While that is a sad outcome, surely it would still be irrational for each person to change their beliefs--they should definitely not believe something that *doesn't* seem right to them in this situation. I just think it's a sad fact that some people (probably most) just have differing intuitions, so that they could only come to agree through irrational means. Nevertheless, that seems like the best we can do.

I went to a magic show. It seemed like the woman was cut in half, but I know she wasn't.

This shows it's possible to assert something that is contrary to your seemings.

When I think of intuition talk, I think of it as an invitation to the interlocutor: "hey this seem true to me, does it also seen true to you?". Because if it does not, then we have to debate the issue. Whatever score I get from my seeming, you also get from yours.