Philosophy and Rigour

Some Problems with the uncritical endorsement of Intimidating Formalisms in Philosophy

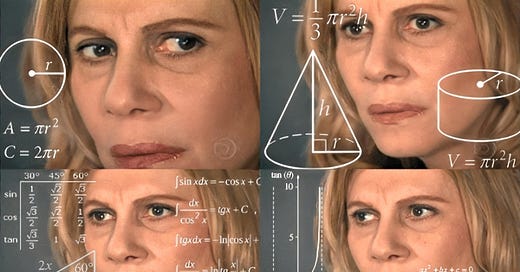

In contemporary Philosophy—particularly the terminally online sort that I am apt to engage with—it is not uncommon to hear words like “prior probability”, “likelihood ratio”, “posterior probability” and “hypothesis” ejaculated as if one had accidentally stumbled into a conference room in some sort of serious scientific discipline. Often (though not always), the people saying these sorts of things have no qualifications in Mathematics since high-school algebra and couldn’t demonstrate college-level Mathematical skills such as providing you with the derivative of a graph of X^2 or telling you what happens if you multiply a matrix by its identity matrix of the same dimension. So, what’s going on here? Why are these people talking this way? Should they continue to talk in this way?

The adoption of formalism in argumentation is nothing new, with philosophers throughout the ages adopting and even debating formalisms. For example, when we look all the way back to ancient Greece we can find many examples such as Stoics deeply engorged in disputes about the correct ways of understanding conditionals and modality, memorising argumentative forms and Aristotelians disputing the valid forms of inference for combining categories of things. None of these were features of the ordinary Lebenswelt of the time but arose as discourses specific to the concerns of those engaged in philosophy.

In Anglo-American analytic philosophical traditions, there has been an obsession with formalism and rigour (‘rigor’ for my less civilised cousins). We can see this in the works of Americans such as C.S.Peirce, and in Europe and Britain with Frege’s new1 notation for interpreting validity, Russel’s innovations with propositional and quantification logic and the various discourses that arose around these works. I shall leave aside the interesting historical exposition for future articles I hope to write, but needless to say, formalism has a long historic provenance in philosophical thought.

Additionally, formalism comprises a significant part of Anglo-American analytic philosophy university syllabi in contemporary philosophy. Students of philosophy departments often pride themselves on their mastery of formal skills. Propositional Logic, Quantificational Logic, Modal Logics, debates about the Metaphysics of Logic, Critical Thinking, Informal Logic, Gluts, truth-gaps, Paraconsistency, Godel’s Incompleteness theorems and Slingshot arguments are all likely to feature somewhere in the thinking of the average philosophy major. The skills requisite for formalism are taught and examined, and the ability to use formalism in the process of linguistic dispute is considered one of the core competencies required to participate in academic philosophical institutions.

Academic Philosophy **(tm)** values formalism. But is this good or bad? I consider there to be both good and bad reasons for valuing formalism. However, in my experience, those trained and enmeshed in the institutions of academic philosophy uncritically endorse the view that formalism is a good thing, with little concern for the downsides and, as such, end up as the victims of the methodological problems that are associated with the adoption of formalism. Here I shall outline my views for and against.

On the good side:

Formalism enables readers to more clearly see the content and reasoning in an argument.

Formalism ensures arguments follow truth-conducive methods of inference.

Formalism enables focused, clear criticism and rebuttal.

I shan’t say much more about these points as I think they are relatively clear and don’t require too much exposition. Additionally, I wish to focus a little bit more on some of the pitfalls of rigour in this piece, as this is a hit piece against my philosophical enemies! (you know who you are)

On the bad side:

Formalism enables cargo-cult philosophising.

The adoption of methods and notations from less contested, more legitimate and well-established fields such as the physical sciences, based on the assumption that if one merely adopts these discourses and goes through the motions of speaking in the same way, without connecting these linguistic activities to other activities of the sciences these discourses natively exist in (such as empirical enquiry and experimental testing), that this will somehow confer the legitimacy and status of the sciences the discourses are at home in, to the philosophy where one talks as if they were practising this science from the comfort of their armchair.Formalism entitles people to hide extremely bad thinking and the adoption of radically implausible claims.

Putting formalism on a pedestal (as I am accusing some of doing) makes formalism some kind of trump-card criterion for philosophical legitimacy. When one adopts this stance, meeting the criteria of some given formalism is a sufficient condition for one’s reasoning on a topic to be considered serious, rigorous and all kinds of praiseworhty-adjectiveness, even if one is arguing for absurd or morally reprehensible conclusions.

If these formalisms are methodological criteria of good philosophy, then we find ourselves having to devote serious time to engaging with the Bayesian-Laplacian argument for flat-earth. The modal argument for holocaust denial and, worst of all, the anthropic argument for god’s existence.

These criteria for philosophical success are precisely what leads to a discipline continuously trapped in intractable disputes about minutia. Those who adopt these criteria can fortify themselves in a labyrinth of consistent claims and proudly pat themselves on the back for their displays of intelligence and ways of overturning ordinary people’s intuitions. It’s precisely this sort of love for idle speculation that earns philosophy a bad reputation with the public and practitioners of other disciplines.

Formalism can be vacuous and empty.

Sometimes, formalisms do very little for the content of an argument beyond dressing up some contentious claim in serious-looking notation; I consider this putting lipstick on a pig. In these cases, the formalism does nothing to further the reader’s understanding of the claims being made in the clearest way possible, but rather hinders understanding. There is a quote often attributed to Nietzsche along these lines - “They muddy the water to make it seem deep.”

As an example of this, take philosophical dream-team Lydia and Tim McGrew’s “The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.” Even that title as a case of needless pretentious obfuscation, what is “of Nazareth” doing there? I wasn’t exactly confused about which Jesus you meant when you wrote your article on Miracles, about a resurrection, in your book on Christian Natural Theology…! This chapter comes after one which includes an intimidating three-page long “proof” of god’s existence using the apparatus of Modal Logic — a proof which I believe shows absolutely nothing of use and the engagement with which is no more impressive or useful than the completion of a Guardian crossword puzzle.Rant notwithstanding. In this paradigmatic exemplification of my claim that valuing formalism and rigour in philosophy is not truth-conducive, Tim and Lydia go on to say, using the power of Bayes:

There are many, specific, first-order issues with the arguments they make which I and my co-hosts get into in our nine-hour treatment of the chapter in Episode 18 of Bad Apologetics. However, I am limiting my focus now on formalism.

Somehow, by chanting the incantation of Bayes’s Theorem over and over again, the McGrews have convinced themselves that updating based on the evidence that [ and this is a paraphrase, though I think a defensible one ]

(a) Texts from 2000 years ago say the words “Jesus resurrected from the dead” (in Koine Greek, of course)

(b) Texts from 2000 years ago say the words “women saw it”

(c) Texts from 2000 years ago say the words “there were 13 disciples who saw it”

(d) Texts from 2000 years ago say the words “A guy called Saul converted”

should lead us to a confidence level nearing absolute certainty, of 0.9999 that a man in some non-specified way supernaturally resurrected from the dead and interacted with people in the ways described such that people (30-120 years later) wrote down these veridical accounts of the happenings. Clearly, doing the really important work here - let’s hope that the Bayesian argument for why you should give this misfortunate Nigerian Prince your bank account details doesn’t land in the McGrews inboxes.

Circling back to the central claim, prior to getting riled up about this abuse of reason, the point I was making was about how excessively valuing formalism entitles people to say vacuous things. In the McGrews case, for example, why use Mathematical notation in this way? Why not do the following?Or, perhaps read the entrails of a pig and see what our subjective intuitions tell us, or just say the following:

"The best explanation of { a, b, c, d } is that Jesus (of Nazareth, not that other one you were thinking of) resurrected. After thinking about it a bit in fact, Im almost certain that he did."

After thinking about this argument long and hard, I am convinced there is no substantive difference between the two. Of course, my way of putting things is far less likely to impress anyone and more likely to prompt a raised eyebrow or two. This is partly why I take it that what’s really going on here, the relevant advantages of doing philosophy in this sort of way are to defend one’s position with the first two bullet points I have classified as bad features of formalism in philosophy.Advocacy of formalism can depend upon and encourage the adoption of epistemically risky and contentious philosophical positions.

Claims about what constitutes good or legitimate philosophy are connected to claims about methodological standards. Claims about good methodological standards are connected to justificatory claims for those standards.

Often (though reader please note that I do not have good empirical data here to say exactly what proportion), uncritical advocates of formalism will adopt all manner of contentious, risky disputed positions in order to justify their commitment to the formalism-supremacist metaphilosophical point of view.

These will include but are not limited to views of concepts and the a priori that are in tension with (and often completely ignore) our best theories in linguistics and cognitive science. Idiosyncratic views pertaining to the methods of rigour being adopted for philosophical purposes—for example, Objective Bayesianism (a minority view amongst statisticians). Novel ways of using the methodology internal to the field these methods are being applied in—for example, in Philosophy of Religion, an entire discourse around “intrinsic probabilities” of concepts has arisen which, as far as I can see, is completely unique to Philosophy of Religion and does not exist in mainstream Statistics as a first order discipline.

A further consideration here is that the requirement to adopt the standards of success internal to the institution of academic philosophy provides a perverse incentive for practitioners of philosophy to rationalise their commitments to these positions that justify the (flawed) methodology of the field. To undermine the field by rejecting the orthodox methodological values would be to not be taken seriously in the field. Not being taken seriously in the field has all sorts of consequences for someone’s ability to go on doing philosophy. For example, one may be unable to get a job in philosophy which enables them to feed themselves and go on thinking about these things. The privileged status of formalism and rigour thereby leads to a selection effect in the field which leaves many philosophers entrenched in a position where they not only adopt certain values about formalism and rigour, but also are committed to other inferentially related claims about the nature of language, perception and mind.

Concluding this nasty hit piece on academic philosophy, I want to balance things out a little. Whilst I am exceedingly pessimistic about the prospect of formalistic rigour for helping to achieve “philosophical progress” (a notion that I find highly suspicious), I do not wish to overstate the case. I do believe that formalism can provide us with tools that can help us clearly communicate ideas and reason about things. It is important to emphasise this word though, tools, and not view formalisms as inevitable, infallible, rigid truth-detecting machinery of reason handed down from the divine logos to mankind.

Some of my best conversations in philosophy, and places where I feel I have made the most progress in clarifying my thinking about things and making sense of phenomena that concern me have come from engaging with people who make this trade-off well. These thinkers both put in the hard work of learning as much as they can about the formal systems we use for thinking about inference, they also contextualise the disputes and methodological issues with these formalisms in their primary disciplines of use. They also don’t elevate these tools to divine status, they don’t brandish the fact they’ve learnt these tools in the face of the less learned, or use them to fortify themselves from criticism in a maze of equations. They put these tools in their proper place, and use them in the service of other values like seeking truth, clarity and understanding.

My aim in writing this piece has been a sort of call to action for philosophers. To recognise where they might be inappropriately elevating formalism, using it to obfuscate or weaponise it. I hope my readers will reflect upon their own relationship to formalism, and consider the ways in which it harms or hinders their pursuit of truth.

Or, perhaps not new. Bobzien (2021) argues that Frege merely Plagiarised The Stoics (https://philarchive.org/archive/BOBFPT). Certainly worth a read if, like me, you take an interest in such minutia.

I agree, especially with the part about the use of Bayes' theorem in philosophy. I understand it can be useful in fields like medicine, astronomy and such. And I am not saying philosophy is a worse field or that we cannot use rigour at all. But in philosophy people often just have a intuition about something and than assign it a rather arbitrary number.

An example would be someone who reflects on the claim "God would want to incarnate as a man so He can relate to us better", finds it plausible and says the claim has a probability of 0.85.

The very intuition about something such disconnected from the human experience such as God and His motivations is suspicious. Assigning numerically precise probabilities to such claims is kind of ridiculous.

I've recently been thinking a lot about some similar ideas. That academic philosophers are limited in their potential by the incentives of academia. That much of the complexity and prerequisite knowledge of academic philosophy (and academia more broadly) exists primarily to convince other people that the author is very smart and special, and maybe to protect their special idea from dissagreement. It seems to me that this type of philosophy will always be pretty much useless because the mountain of prerequisites virtual guarantees that almost nobody will invest the time required to understand or engage. If you can't present your ideas in a way that other people can understand, you don't actually understand the idea.

If you follow math research at all, you will often see mathematicians apply probabilistic thinking to the likelihood of new proofs being true. The longer and harder it is to understand a proof, the less likely it is to be true, and the more likely it is that there is some minor error which undermines the proof entirely. This is because there are lots of people who's goal is really to prove their own intelligence.